Debbie Harpham

by Ellen Meeropol

Cats have long been associated with books; they are our companions as we read them and write them. The image of a person curled up on a comfy armchair with a book and a feline companion is iconic, not to mention delicious. Another equally iconic but less practical trope is the cat sprawled across a writer’s computer keyboard. Bookshops often have a store cat; felines are a common element of the ambiance of reading, independent thinking, and appreciation for the literary life.

Felines are no strangers as characters in stories either. From Dr. Suess’ The Cat and the Hat and Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire Cat to Don Marquis’ Mehitabel, from Haruki Murakami’s Mimi in Kafka on the Shore to Lilian Jackson Braun’s crime solving cat and Hermione’s companion Crookshanks. From Behemoth in The Master and Margarita to Holly Golightly’s nameless tiger tom in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Perhaps because of their complex intelligence, stubborn independence, and elusive personalities, cats as characters lend themselves to metaphor and magnitude.

In my experience, most writers who share their homes with pets in real life are either dog people or cat people. The same is true for writers who regularly include home-dwelling animals as characters; we tend to invite either dogs or cats into our stories. An exception is my writer friend Jacqueline Sheehan, clearly a dog-lover in her novels (Cooper the black lab is a great favorite with her readers) who lives with two cats. One is named Cooper, just to keep us on our toes.

I like cats. In person and in fiction. My current feline companion is an elderly gray tabby named Cory (short for Coreopsis or Coriander, depending on whom you ask.) But it wasn’t until a friend observed that each of my novels has a feline character that I started thinking about how household felines function in my novels.

The roles of my cat characters have evolved over the years. In my first novel, two cats live in an oddball cult—a black cat named Bast, for the Egyptian goddess worshipped by the human members of the household, and a yellow cat named Newark, for the city. Bast is killed by people hostile to the cult, sacrificed to the requirements of the story. Yes, some readers were very unhappy with me. In my second book, the cat is named Sundance, and although he never appears in scene, thinking about his thick yellow fur keep the main character strong while she is held hostage by security forces run amok. The cat’s name and the film reference help the main character outmaneuver her captors, playing a crucial role in the plot. Bast-the-cat returns in my third novel, which opens with a flashback to the cat’s funeral when his boy companion, now a college student, was nine years old. The other main character, Flo, has a gray cat named Charlie, who shares his name with Charlie-the-man, who never knew he fathered Flo’s child. Charlie-the-cat dies in the accidental fire that spells the end of Flo’s independent living. Hmm, another sacrifice. And another shared name. Mustard is a yellow kitten in the opening scenes of novel #4. He moves with his family when they flee Detroit and dies a non-violent death from old age. Whew.

I seem to be partial to yellow cats, as another one shows up in my new novel. This time, the cat is a sort of oracle, choosing to live in the station wagon of a homeless woman. The woman names her Canary because she warns of danger. Canary doesn’t meow, but she has a “unique repertoire of sounds: contented chirps, rumbling purrs, and guttural growls of warning.” She’s not my first literary cat who vocalizes in unusual ways. Newark had an odd purr, “harsh and sputtering like a tractor.” Cats can’t speak in words, but their voices can be significant.

Characters, whether human or feline, often refuse to follow author directions, fetch toys or plot devices, or be herded in any way. But looking back at the cats who keep me company as a fiction writer, I notice that they have demanded, and achieved, increasing agency in each novel. In their own fiercely independent and often cantankerous ways, my feline characters have evolved from sacrificial victim in the first novel to oracle in the fifth, gaining power with each book.

That doesn’t surprise me at all. In my world, cats belong on laps and in books and they can exert power over the plot. On their own terms, of course.

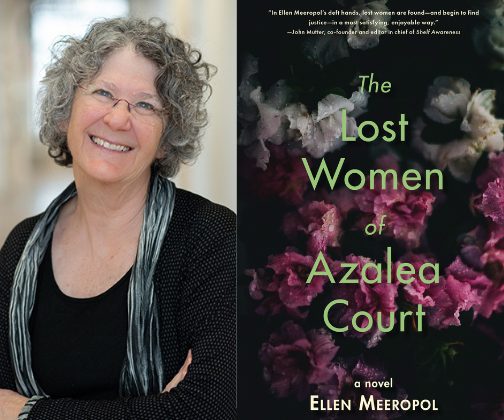

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Ellen Meeropol is the author of the novels The Lost Women of Azalea Court, Her Sister’s Tattoo, Kinship of Clover, On Hurricane Island, and House Arrest, and is guest editor of the anthology Dreams for a Broken World. Recent and forthcoming essay and story publications include Lit Hub, Solstice, Lilith, Ms. Magazine, The Boston Globe, and The Writers Chronicle. Her work has been honored by the Women’s National Book Association, the Massachusetts Center for the Book, PBS NewsHour, the American Book Fest, and Publishers Weekly. She earned her MFA in fiction from the Stonecoast program at the University of Southern Maine. She is a founding member of Straw Dog Writers Guild and leads the Guild’s Social Justice Writing project. She lives in western Massachusetts.