Debbie Harpham

by Kitty Zeldis

Every novel has a backstory, but The Dressmakers of Prospect Heights has two. It was my job to weave them together, rather like braiding a challah bread.

The first of these was New Orleans, a place that figures importantly in the background of one of the central characters, Beatrice Carr. I first visited the city in 1988 and fell instantly in love. The look of it, the melange of cultures—Southern, French, Spanish—the food, the music, the history, all contributed to its appeal. While I was there, I learned about Storyville, or The District as it was also called—a designated area in which prostitution was legal during the years 1898-1917. Not only legal, but on full and lavish display, as Basin Street, which was across from the railroad station, was lined with brothels, one more opulent than the next. Their owners—often women—became celebrities of the demi-monde, important individuals who wielded influence and power. Prostitution was a huge business that in turn helped fuel other businesses as hundreds of musicians, cooks, waiters, servants and more were needed to keep the wheels turning. Guides to sin city were published and these so-called Blue Books, widely available at newsstands and tobacco shops, were designed to inform the constant influx of tourists and pleasure seekers about the vast array of choices that were available. Although filled with ads for the various houses of ill repute as well as for restaurants, cafes, clubs etc. the Blue Books were chiefly a listing of all the prostitutes working in the area.

I saw some of these books displayed in the historical society, and one of the entries read like this: Caucasian, twenty-one, Jewish. Jewish! This was news to me. As an Ashkenazi Jew myself I had heard many immigration stories, stories in which those who were chased out of the old country found their way to a new one. But the story of a Jewish prostitute in New Orleans was not something I’d encountered before and since I am a novelist, not a historian, I decided that I wanted—no, needed—to imagine my way into such a life and in doing so, write it. I set about researching, trying to make the period real in my own mind so that I could make it real in the minds of my readers. I read all that I could find, looked at scores of old photographs, and made another trip to New Orleans. Soon a character began to emerge—a young Jewish woman, far from home and cut off from family and friends, who finds herself pregnant. Dismissed from her job and without a husband or home, she finds work in a brothel, first as a maid, later a prostitute and eventually a madam, with a house of her own.

The other strand of this story—or part of the challah if you will—comes from my grandmother, Tania Brightman. She was an unhappy, difficult woman, prone to terrifying outbursts of rage. She was also a troubled and even traumatized soul who did not fully understand the impact of her tragic past and how it had shaped her. Tania was born in Russia to an atypically affluent Jewish family. Her father was a tanner, a profession Jews were allowed to have because it was so revolting (a chief component in the process was urine). He was murdered in mysterious circumstances when my grandmother was a small child. Her mother’s response was to take poison, but she survived the attempt (my grandmother remembered the burns around her mouth) and then, leaving her two tiny daughters home alone, went out day after day to sell whatever she could from their fine house, eventually amassing enough money to take her youngest children first to Riga, and then to New York.

I was not at all close with my grandmother, and found it easy to distance myself from her; we lived in different states. So when she died, I was wholly unprepared for the flood of grief and regret I felt. I wished, oh how I wished, I had been more patient, more understanding, more loving. Of course it was too late to make amends to her. But writing is a form of redemption, and it was through my writing that I could reframe her story, giving her the dignity and the compassion that I’d withheld from her when she was alive. I looked at her early life in Russia and used significant events in her past—the murder of her father, her persecution as a Jew—to shape my character. And although she never became a prostitute or madam, and never even visited much less settled in New Orleans, it is her spirit that animates the character of Beatrice Carr and I can only hope I have done both of them justice.

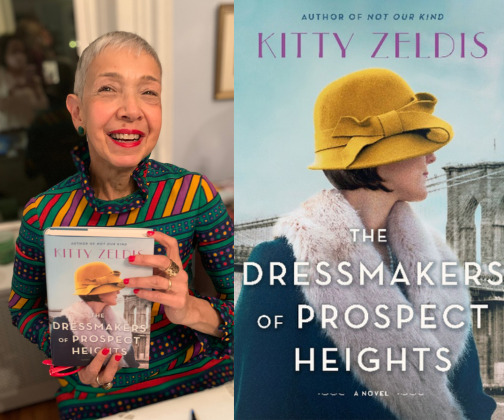

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Kitty Zeldis is the author of nine novels and nearly forty books for children. Her two latest novels are both works of historical fiction. NOT OUR KIND is set in 1940’s New York City and CT, and deals with anti-Semitism in the post-war period. THE DRESSMAKERS OF PROSPECT HEIGHTS is set in the 1920’s and is about a Russian Jewish woman who goes to New Orleans where she becomes a prostitute and then a madam.

Author visits with Kitty Zeldis coming soon via NovelNetwork.com.